Since 1912, Motorcyclist has celebrated new motorcycles and the riders who do remarkable things with them. But today, we’re acknowledging used motorcycles that suck. Specifically, motorcycles that suck, according to you, the loyal readers of Motorcyclist.

We asked readers on the MotorcyclistMag Facebook channel to tell us about the worst motorcycles they’ve owned, and you answered the call with more than 200 comments. Motorcyclist makes no claim or legally defensible arguments as to the veracity or nature of the sucking motorcycles in question. We report, you judge.

Surprisingly, not many ‘80s-era tariff bikes got mentioned. Nor did many dirt bikes. Throughout motorcycling history, too many motorcycles to properly list have sucked. So consider this a brief account of the most noteworthy bikes that have sucked, according to you.

Full disclosure: The author owns or has owned three of the bikes on this list: a 1974 Honda CB360T, a 1975 Kawasaki H1F, and a 2009 Buell 1125CR, which he currently owns and loves.

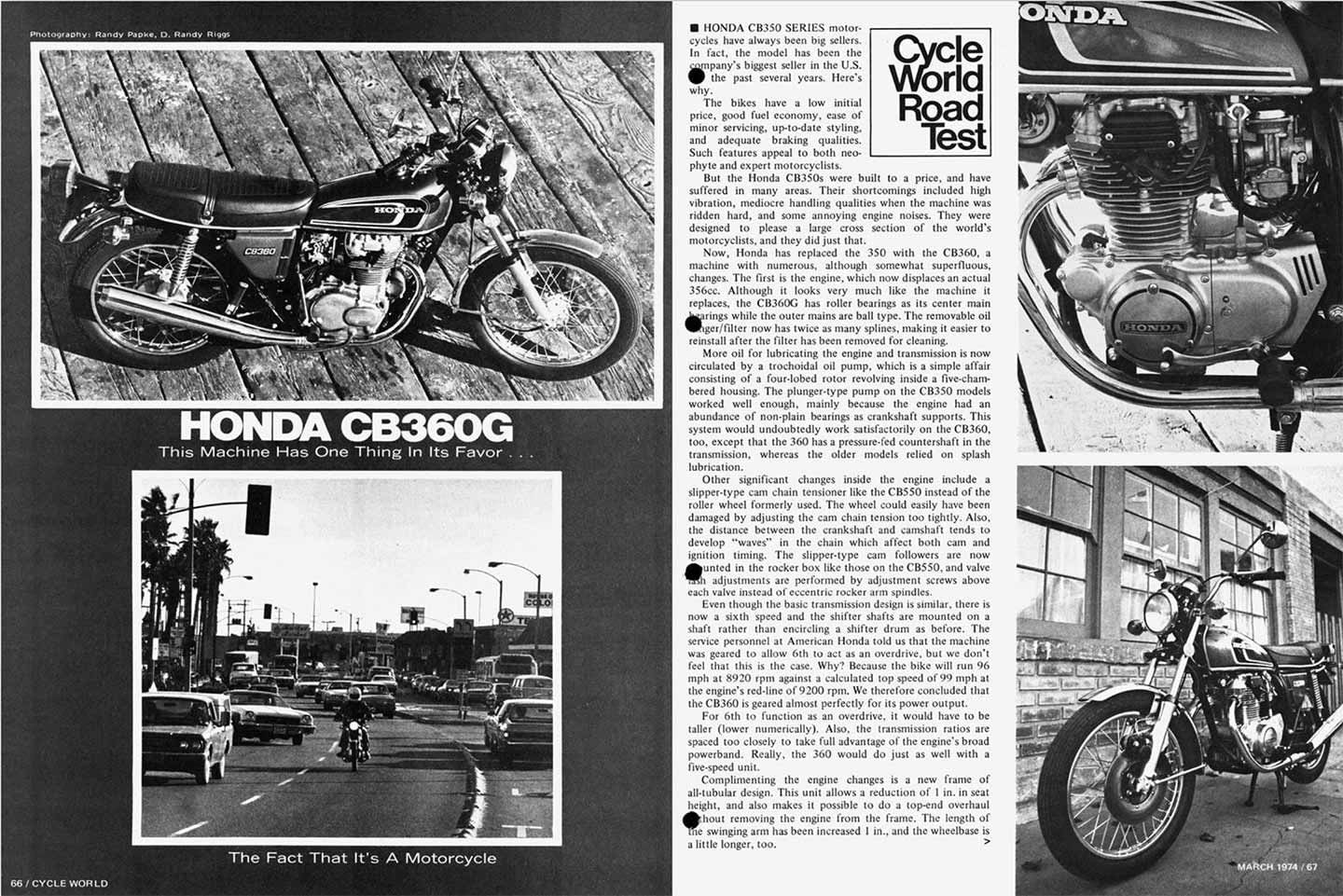

1974–1976 Honda CB360T

Even Big Red whiffs once in a while. The CB360T isn’t that bad a bike, it’s just that the preceding 1968–73 CB350 was one of the better motorcycles ever made. Then, in 1974 Honda decided to add 31cc, 29 pounds of weight, and 2 less horsepower. A poorly designed cam-chain tensioner added to the fun, occasionally getting sucked into the crankcase with destructive results. A recall finally made CB360s reliable, in addition to slow and boring.

Worse, few if any parts were analogous to the beloved CB350. The one upside is they’re the only cheap ‘70s-era Honda left. In basket-case form, they’re often given away. For those who love subframe hoops and other brat-style nonsense, it already has one, so that’s something. But otherwise, the CB360 is pointlessness on wheels. Noted Honda enthusiast Bob Burns has been fighting the scourge of used CB360s for years. “Worst bike Honda made in the ‘70s. They could’ve just put a six-speed in the CB350G and called it a day.”

Dishonorable Mention: 1972–1974 Honda CB350 Four

Flush from the success of its revolutionary inline-fours, Honda decided to extend the treatment to the 350 platform, giving us the CB350 Four. Riders liked the smoothness of a four, but overall it was gutless and uninspiring. To help keep up with its faster, lighter CB350 twin, weight was obsessively kept down, leading to thin-walled exhausts that rusted quickly. Reader Douglas H. sums up the CB350F’s charm: “All of the weight and complexity of a larger four-cylinder bike with less power than an equal displacement twin.”

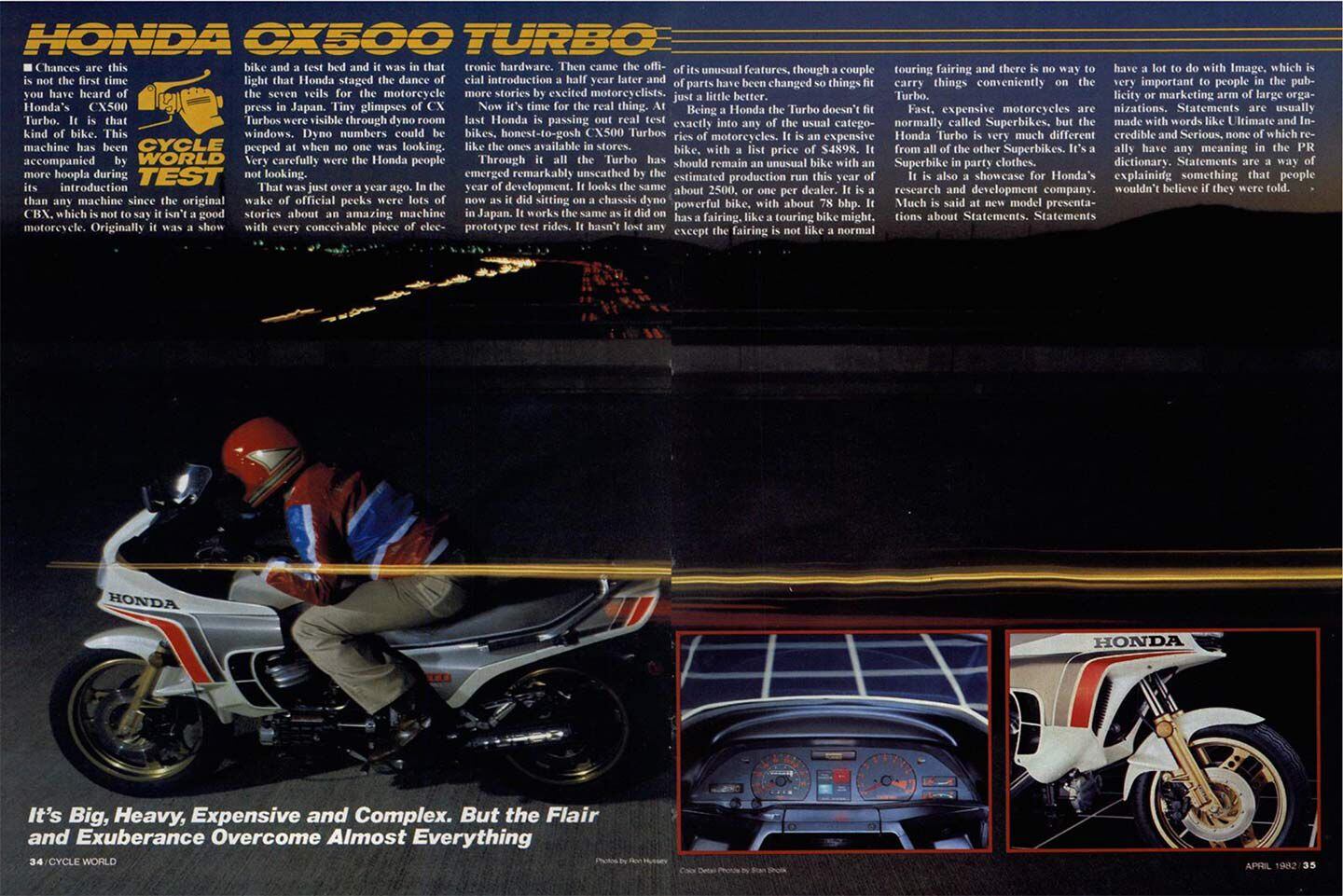

Dishonorable Mention: 1982 Honda CX500 Turbo

Made for a single year before becoming the CX650 Turbo, its 19 psi of turbo boost nearly doubled power output when it kicked in. The key to rider longevity was remembering when that happened. Ultimately, a high MSRP and insurance rates were the real danger, with unsold models reportedly donated to technical schools. Reader Ted E. reflects on his time with the CX500 Turbo: “While I loved my Honda CX 500 Turbo it had an appetite for stators and was difficult to service, being at the rear of the engine which required removal to service.”

1977–1979 Harley-Davidson XLCR

Although coveted today, the 1977–79 Harley-Davidson XLCR suffered the same cursed birth as all AMF-era Harley-Davidson products in the ‘70s. The first bike penned by Willie G. Davidson, it was a striking, marked departure from period Motor Company design orthodoxy. But ultimately, it was a ‘70s era Harley in all the wrong ways. Labor disputes with new management meant unreliable motorcycles right out of the crate. Brakes were bad and its long wheelbase meant it was a pig in turns. The “Siamese” exhaust header supposedly added a few ponies, but the Ironhead mill was already maxed out on streetable power.

Worse, the styling was out of step with H-D consumers. Paltry sales numbers are a big reason they’re collectible today. Reader Bob H. experienced a particularly bad example: “I had a 1977 XLCR I bought new. Transmission failed twice, the fiberglass parts shook their metal anchor parts into pieces. Taillight snapped the plastic backing piece off, dragging itself on the rear tire.” Fellow reader Matt L. also chimed in: “I paid $2,999 out the door for mine. It had RUST under the paint on the tank that they refused to cover under warranty.”

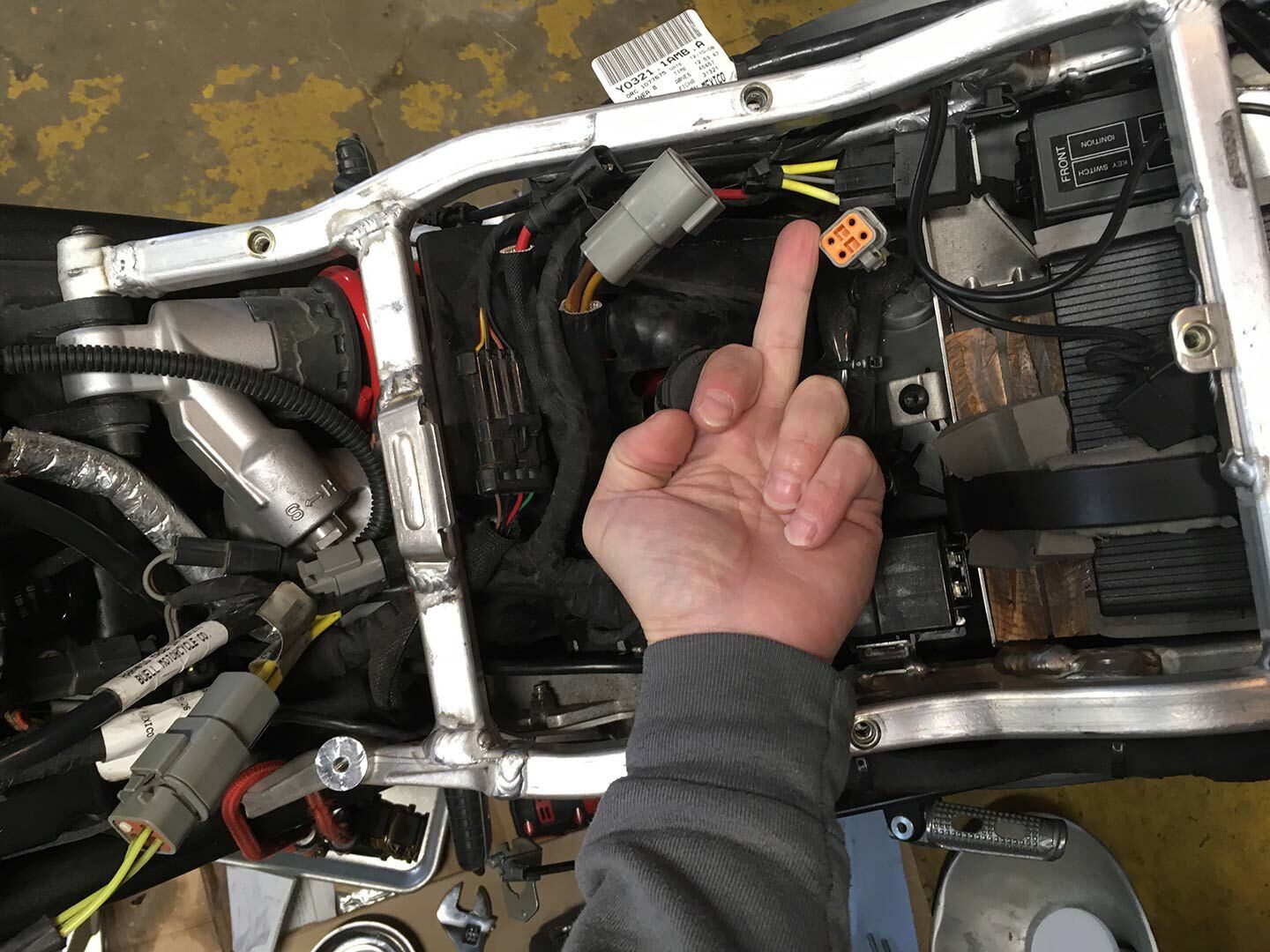

2008–2010 Buell 1125R/1125CR

This one hurts. But it’s your forum, not ours. And even the most stubborn Buellistas among us will take this on the chin. The swan song of Erik Buell’s 25-year vision for American-made sportbikes, the Buell 1125R and 1125CR had roughly three Achilles’ heels. The stock charging system wasn’t up to the task, leading to fried stators, regulators, and rectifiers. Even when replaced with more robust H-D units, always-on radiator fans meant keeping nervous watch over battery voltage in any stop-and-go traffic. The 146 ponies at the crank plus Erik Buell’s chassis concept meant plenty of fun in the country, once the above-mentioned was fixed. But the 1125 was fated to become a minor cult item in Buell’s minor cult following.

Worst of all, Buell went bankrupt in 2009, meaning parts availability went downhill after October 30, 2009. Beleaguered H-D dealerships were stuck with warranty claims on a brand they didn’t even sell anymore. Reader Joe H. offers a eulogy of sorts: “Buell 1125, fun bike. But it had issues and couldn’t get parts to fix it once H-D stopped supporting it.”

Dishonorable Mention: 2000–2009 Buell Blast

This Buell Blast was a punchline to a joke owners didn’t find very funny. Erik Buell famously crushed a Blast into a cube, by way of announcing the model’s demise. But the Blast laughed last when Buell closed its doors two months later. A 500cc OHV thumper sounds fun on paper. But it was basically a pig-slow Sportster motor cleaved in half with 34 hp to show for the millions invested in development by Harley-Davidson. To be fair, it was quite tuneable, with some custom examples reaching 50+ hp.

With fairings made with Surlyn plastic (also used in golf balls and Dodge Neons), the Blast was cheap to repair if dropped. But some owners never bothered picking them back up. Reader Ben A. swears it wasn’t actually his bike: “Technically it was my wife’s, but man, was it a POS.”

2017–Present Suzuki GSX250R

While the rest of the motorcycling world went to 300cc or 400cc years ago, usually with a single cylinder, the twin-cylinder 248cc Suzuki GSX250R soldiers on. Suzuki often reinvents motorcycling as we know it. But between these triumphs, they sometimes just punch the clock. The 2017–present Suzuki GSX250R showed up a full four years after the Kawasaki Ninja 250 went to 300cc, two years after the 300cc Yamaha YZF-R3, and six years after Honda’s CBR250R in 2011.

To be fair, 250cc bikes are much loved (and bought) in Asian and European markets. And really, does 50cc (or so) make that much difference to the novice rider? Isn’t a tiny twin basically as good as a small/midsize thumper? Shouldn’t America be happy it gets capable small-displacement bikes at all? According to reader Scott C., we deserve more: “All the weight of 400 and size of a bigger bike with the power of a 250.” This country wasn’t built on just being content. We applaud your discontent, Scott.

Incidentally, the 1991–1992 Suzuki GSX250S, based on the Hans Müth–designed GSX1100S Katana was a rare sight in the states, but quite popular in Japan. It had a liquid-cooled, inline four-cylinder engine with 16 valves. And let’s not forget the pocket-rocket 1988 Suzuki GSX-R250, part of that late-’80s generation of high-revving, small-displacement fours. 17,000 rpm, here we come.

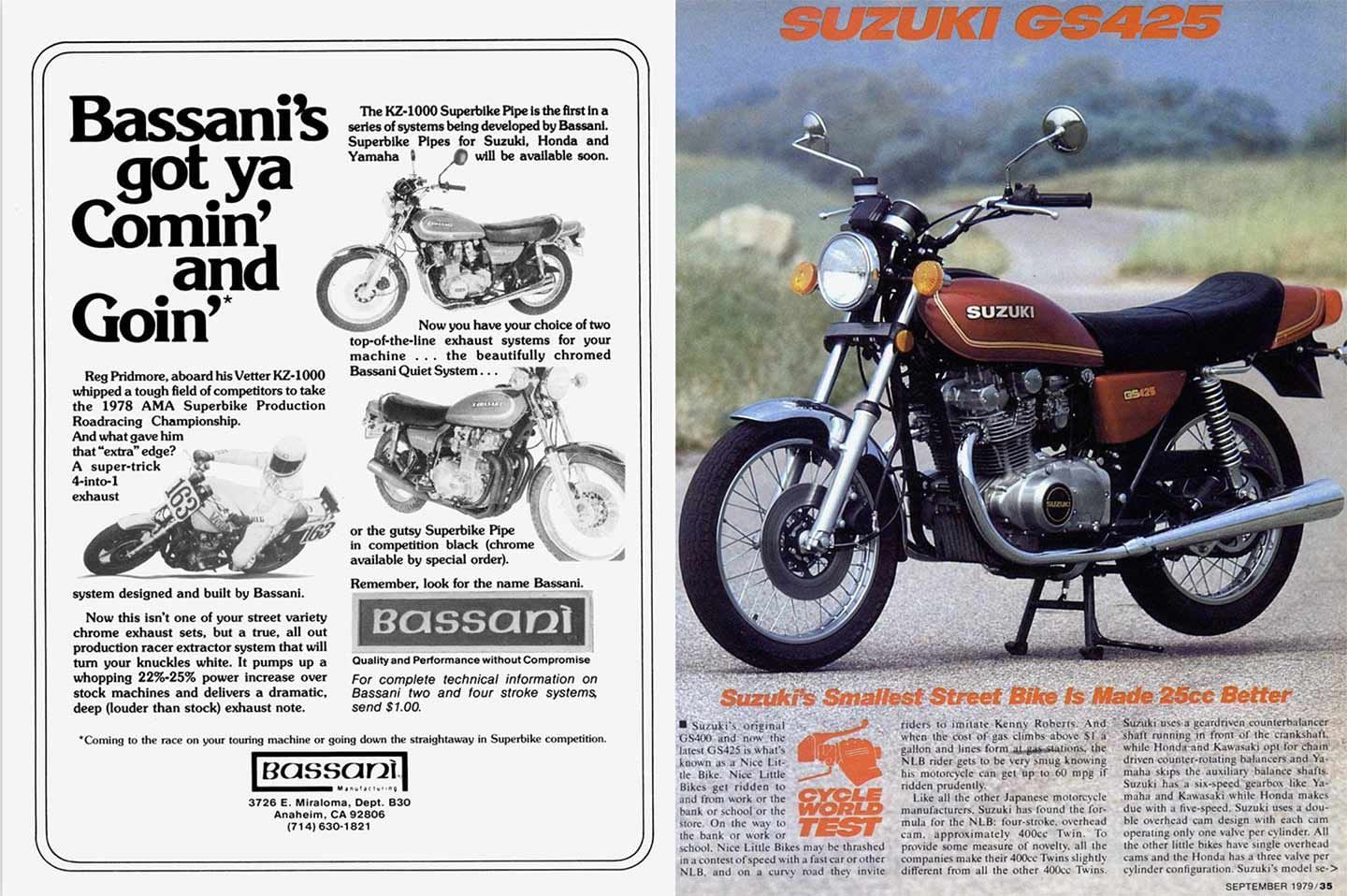

Dishonorable Mention: 1978–1979 Suzuki GS425

Question: What can you say about a model that bested the GS400 by just 23cc and only lasted two years? Reader Steve C. will field this question. Answer: “It rode like a camel, it was awful.”

2003–Present Ducati Multistrada

The 2003 Ducati Multistrada was a bold move. Previously, riding a Ducati involved acts of contortionism and prostration. But the Multistrada offered things like “comfort” and “flickability” atop an upright perch, with a semblance of wind protection. Early Multistradas had issues with hard seats, a small tank, suspect wind protection, and a short sidestand. But on the whole, it was a winning concept that survives to this day.

The Pierre Terblanche design stacked both headlights, as did the Ducati 999, a look that was panned by most. But kudos to Ducati, they stuck with it until the 2010 redesign. That said, two Motorcyclist readers nominated their Multistrada for Worst Bike Owned. First up, previous owner Todd S.: “Despite how much people hated its looks, I always found it to be rather attractive. But I got blasted by wind everywhere, even on my back. And it was underpowered. After less than 1,000 miles, I traded it in happily for a Triumph Sprint. Oddly enough, I have a ‘22 Multi now, and it’s the best bike I’ve ever had the privilege of owning.”

Next up is Ken H. with his 2013 Ducati Multistrada 1200 S Touring. “It was brilliant when it worked, but it had too many electronic gremlins. Issues included fuel tank swelling, fuel sensors that broke every 2K miles, repeated ABS sensor failures, heated grip failures, and a dash module that was glitchy. The factory initially refused to honor the warranty. I had to write a nasty letter to the CEO to get the fuel tank replaced. But at least to their credit they did fix the fuel tank. Just not the other stuff.”

1978–1980 Triumph T140E

In hindsight, buying anything from Triumph in 1979 was an exercise in magical thinking. But late-’70s Triumphs do have one thing going for them: They weren’t the dodgy 1983–85 models assembled from leftover parts after Meriden closed for good. But overall, ancient production tooling, zero R&D budget, and a customer base in freefall all spelled Triumph’s doom by 1983.

In 1978, all that was left to do was slap lipstick on the pig known as the Triumph T140. Updated trim, wheels, electricals, and brakes were all the upgrades Triumph could muster. Electric starting wouldn’t be offered until 1980. The 1978 Triumph 140E model’s emissions controls (the “E” in 140E) provided the only update to Triumph’s aging 750cc mill. Reader Dave R. worked through lingering trauma long enough to tap out these words about his worst bike: “By far my 1979 Triumph T-140E.” Rest easy, Dave. That Bonnie can’t hurt you anymore. Unless you still own it.

Dishonorable Mention: 1997–1998 Triumph T509 Speed Triple

Many people love Triumph Speed Triples. But nobody came to the T509′s defense when it was nominated for Worst Bike Owned. Maybe it was first year fuel-injection issues? Or teething issues with brakes? Perhaps owners with the 855cc motor saw that 1999 owners get an upgraded 955cc engine with 130 hp, and were miffed. Whatever the case, Ade A. condemns the 1997 Triumph T509 Speed Triple in no uncertain terms: “It’s been used as a shelf for over 15 years now, and it’s better as a shelf than it was as a bike.” Bikes make terrible shelves, so that’s really saying something.

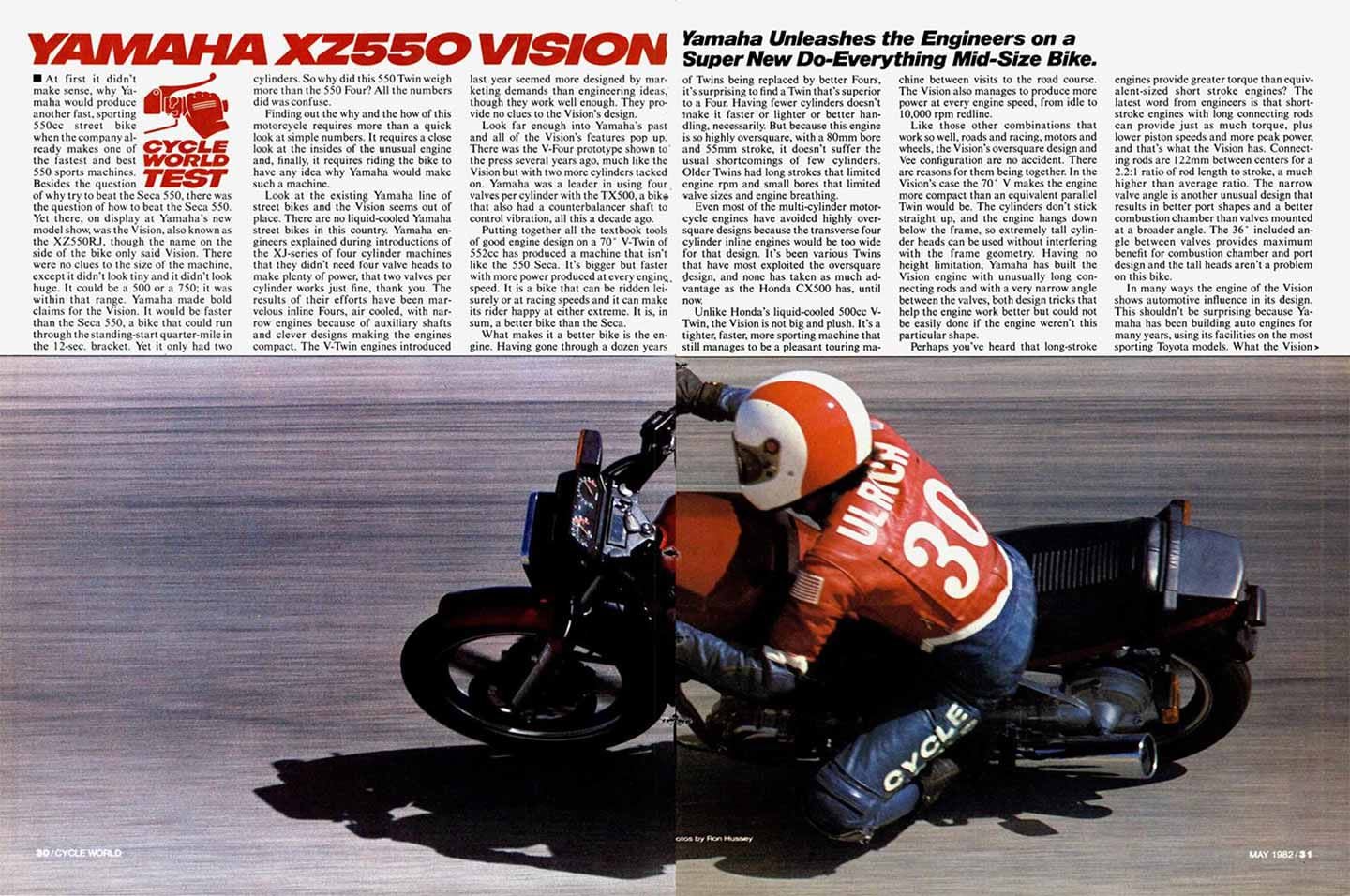

1982–1983 Yamaha XZ550 Vision

“Vision” is a funny name for this motorcycle. Yamaha’s vision became a reality, but not one shared by many paying customers. The Yamaha XZ550 Vision’s styling hinted at a sporty cafe racer and sporty tourer, but it didn’t land either look really well. It had all the sexy bits of a bike designed from scratch. Its 552cc liquid-cooled 70-degree V-twin mill was torquey all over the tach, with nimble and quick handling to boot.

But it was an answer to a question no one had asked. A small team of designers were responsible for developing the Vision, reportedly without dealer input or advice from the bean counters in marketing. The 1983 model was all-in on a sport-touring package, with a fairing and improved carburation. But reader Greg H. was wholly unmoved. All he had to say about his Vision quest was, “1982 Yamaha Vision. Sorry Yamaha.”

Dishonorable Mention: 1975–1978 Yamaha XS500

By the time Yamaha had perfected its 500 twin in ‘78, the party was over. They say the last year of any model is the best. But in life, your best usually comes too late. Starting life as the 1972 Yamaha TX500, early ones had heating issues due to anti-vibration crank balancers producing oil froth and aeration. They also had oil leaks from the head. Valve seats warped and cylinder heads cracked. Yamaha later produced a smartly revised motor with integrated cylinders and cam boxes.

But ultimately, it was a 500 twin with just 34 ponies’ worth of bang for the buck. If Pulitzer gave out awards for motorcycle writing, previous owner Andrew A. would win something for this gem: “Utter heap! Slow heavy land anchor… Hewn from marble and it handled like a truculent hippopotamus. Ghastly beast.” Andrew, we’re stealing “land anchor” for future use. Look for royalty checks soon.

1969–1975 Kawasaki H1500

The Kawasaki H1 had numerous “worst” qualities. But sub-13-second quarter-mile trumped everything for most riders—until they hit the twisties. The frame design was no worse than its contemporaries. But the short wheelbase of early models, an engine mounted too far back, and period rubber tires meant riders were often spooked by unpredictable handling and, of course, unintended wheelies. The 1972 H1C got a frame redesign and the 1973 H1D got a longer wheelbase and less horsepower, which lasted until the 1976 KH500 variant.

But the word was already out. The 748cc H2 variant is more commonly called the “Widowmaker,” but early H1 owners also muttered the term under duress. If you’ve got a running H1, you can easily turn it into a couple of mortgage payments. Prices are high, with ‘69–72 models fetching five figures in restored shape. But back to the whole fear thing. Reader Shane G. shares his brief experience as owner: “Bought a clean example that was not running. Fixed it up. Rode it to work. Got a friend to take me home. Put it up for sale. Fun engine but the scariest chassis I’ve ever ridden.” Bob B. also fondly remembers his time aboard an H1 with these few words: “High speed death wobbles.”

1985 BMW R80 G/S Paris Dakar

While many Airhead aficionados would love to throw a leg over a BMW R80 G/S Paris Dakar, previous owner Rick H. is not among them. He took the time to detail why his G/S was the worst of the nine BMWs he’s owned, and Worst Bike Owned, overall. Motorcyclist combed our vast archives and consulted our army of cognoscenti about R80 G/S problems and issues, but didn’t find much. The air pulse system did tend to overheat exhaust valves over the course of 30K miles or so. It passively injected fresh air from the airbox into exhaust ports, eliminating the need for active “smog control” components. Otherwise, it was the usual gamut of shaft-drive watch-outs and deferred maintenance issues.

However, people who love the R80 G/S didn’t write to us and Rick H. did. So let ‘em have it, Rick. “The worst was my new 1985 BMW R80G/S Paris-Dakar. In the two years I owned it, the bike suffered dozens of repeated failures of brakes, transmission, electrical, seals, paint and frame corrosion, and three failed master cylinders. I took a 73% loss when I traded it for a new ‘87 CBR600F Hurricane.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G2D52LQJIBD6ZBGWSPTWLOYZN4.jpg)